The Bullet That Echoed Through Generations: Remembering Slain Grant County Sheriff Melbourne Lewis

Local News January 9, 2026 Staff 0

In a New York minute everything can change. In a South Dakota minute everything can also change. It happened to the Melbourne Lewis family of Milbank on Wednesday, July 30, 1941.

Grant County Sheriff Melbourne Lewis was gunned down that day in Milbank and died at 5:30 p.m. With a single crack that many townspeople going about their business might have mistaken for thunder, Sheriff Lewis was dead. He was just shy of his 35th birthday, and he left behind his young wife Florence and four children – Betty Lou, 12; Marwood, 11; Neil, 7; and Larry, 2.

Melbourne’s killer was Clifford Hayes (Haas), or something similar. Hayes had been adopted and not even Hayes was sure of his last name. At one time, he even referred to himself as Eugene. Hayes was a 30-year old native of Buffalo, Minnesota, who had been imprisoned since the age of 14. He had most recently served eight years for burglary. The day before the shooting, Hayes had been released from the South Dakota Penitentiary in Sioux Falls and had made his way to Aberdeen. It is believed he planned to ride the rails to the west coast from the Hub City, but the trains were running late, and Clifford was impatient. Instead, he hopped in a boxcar going in the other direction. When it stopped in Milbank, he jumped off and walked into the Gambles store on Main Street, where he purchased a .22 rifle and a box of bullets.

Accounts of that day say shots were being fired at cars on US Route 77 (now Highway 15) near Lake Farley, and a group of boys reported a stranger wandering around town toting a gun. Later that afternoon, things turned tragic.

Responding to the complaints, the Milbank Police Department and the sheriff’s office tasked a few men with finding the stranger. Sheriff Lewis, Chief of Police John E. Farley, Grant County Commissioner Frank Miller, and Deputy United States Marshall Ben E. Hughes of Aberdeen, made up the group. They picked up the stranger’s trail just one block north and one block west of the railroad tracks at the end of Main Street. The Texaco station was located there, and the Charles McGiven family lived just behind it.

Hayes had concealed himself in a lilac bush in the McGivens’ backyard, between the woodshed and the house, and Sheriff Lewis demanded that Hayes come out of hiding. Bud (Ideen) Nelson, 23, who was working at Texaco, later said he believed the gunman saw the Texaco star embroidered on his shirt and mistook him for police. Hayes shot, and the bullet ripped through Nelson’s shirt under his arm and hit a customer, 12-year-old Lyle Tillemans. It lodged in Tillemans’ chest bone. Sheriff Lewis saw the young man had been struck, and in a bold act of bravery, he stepped into view. Hayes immediately ripped off another shot and hit the sheriff in the chest. He killed Melbourne instantly.

In the melee that followed, Hayes escaped. As it happens with many crimes and tragedies, and considering this one happened nearly 85 years ago, details of what ensued vary. Research revealed that instead of hightailing it out of town, Hayes approached the nearby Dan Conright home. He hid his gun in a sweetcorn patch and knocked on the door to ask for a glass of water. After Mrs. Conright gave him a drink , she noticed him leaving her yard with a gun. Although she was unaware of the shooting, she decided to alert the authorities.

Meanwhile, Hayes continued on his way and found another service station known as Vandervoort’s, where he purchased and drank two bottles of Coca-Cola. J.T. Harvey, Harold Robel, and Robert Hunquist were also said to be at the station. (Local lore includes Dr. D.A. Gregory in the list of customers there at the time, but it is more likely he entered the story as the physician who removed the bullet from Tillemans.)

Men who also planned to join the posse stopped at Vandervoort’s hoping to borrow a gun, but Vandevoort could only provide some shells. The men left, but soon returned with a description of the gunman to ask if he had been seen. As the story goes, Harvey pointed to Hayes who had remained at the station and said, “There’s your man!” Hayes was captured without a fight and was transported to the Milbank hospital, where witnesses, including the recovering Tillemans and Nelson, identified him as the killer.

The law enforcement officers involved in apprehending Hayes determined it was too dangerous to detain Hayes in the Grant County Jail, due to community outrage. They transported him to Sioux Falls that night.

Hayes’ trial was held five days later on Monday morning. He was questioned in court, “Did Mr Lewis shoot at you?” He answered, “No, but I thought he was going to plug me.” Hayes then entered a plea of not guilty and said, “I won’t go back to prison. Life in prison is not worth living.” However, he later changed his plea to guilty and requested the death penalty.

One thing no one disputes is that just one bullet had stopped the heart of Sheriff Lewis, but that same slug had grazed every heart in the Lewis family and ricocheted into the community on a path that kept going for miles and generations.

Melbourne’s funeral is believed to have been the largest in the history of Grant County. Estimates say about 1200 to 1500 people attended the service at the downtown Methodist Church (Parkview) now the current site of Wells Fargo Bank.

So many people arrived from across South Dakota and beyond that cars were parked seven deep across Main Street, and speakers were set up in the basement and parking lot of the church to broadcast the service.

Approximately 2000 mourners had also passed through Mundwiler’s funeral parlor on Main Street during the visitation.

Friends, family, and law enforcement came from far and wide to pay their respects, not only to Melbourne and his young family, but also to Melbourne’s father William, William’s three brothers – Clarence, Buck, and Clifford – and William’s sister, Lulu. Melbourne’s mother Mary had died in 1927, and Melbourne’s sister, Pauline, had passed away the previous March from complications of an ear infection.

In spite of the anguish Florence must have been feeling, upon Melbourne’s unexpected death, she became the acting Grant County Sheriff. The deputy sheriff, however, assisted her and also carried out many of the field calls.

Florence was thrust by fate into the ranks of law enforcement – a career not chosen by women in the 1940s– and into a job that she knew had killed her husband and the father of her children. Nonetheless, she stepped up to serve diligently and honorably. Florence’s new role meant there was little time for heartbreak and even less time for conversation. She had a family to feed and big shoes to fill. The safety of the community had become her responsibility.

Florence finished Melbourne’s term as Grant County Sheriff. She then took on the job as the jailer. After that, she was elected Clerk of Courts for Grant County, an office she held for 35 years. While raising her young brood alone, Florence served as the secretary and treasurer of the Grant County Republican Party for 32 years, from 1942-1974. She also managed to carve out time to attend and serve as the president of the Professional Women’s Club in Milbank

Today, descendents of Melbourne and Florence are quick to agree that, even amongst themselves, the Lewises rarely if ever discussed the day of Melbourne’s death. Sheri Lewis Wendland of Milbank, Melbourne’s niece, said, “Aunt Lil (wife of Clarence) , Aunt Florence, and my mom would get together quite often, but they never talked about the tragedy.”

Melbourne “Mickey” Lewis, Marwood’s son who recently moved back to Milbank, agreed, “My dad didn’t say one word.”

Lori Lewis Dockter of Milbank, Neil’s daughter, said, “If we asked a direct question, our dad would always answer it. Nothing more. But, he always carried Grandpa’s obituary in his briefcase.”

“Detective magazines of the era picked up on the story, though, “said Neil’s son Steve, also of Milbank.

“But mostly it was a mystery, “ Lori clarified. “And we kids were always curious to read everything we could find on it. Grandma Lewis just didn’t talk about it.”

“It was the 40s and the tail end of the Depression. Everyone coped with it in their own way,” Mickey explained. “My dad (Marwood) was 11 years old, and he was working on Main Street helping to pour concrete the day his dad was killed. Four years later, Dad was into boxing. That was therapy in those days. He turned to boxing, and by 1946 he was the South Dakota boxing champ at 112 pounds.” The family all agreed Melbourne and Florence’s kids were tough.

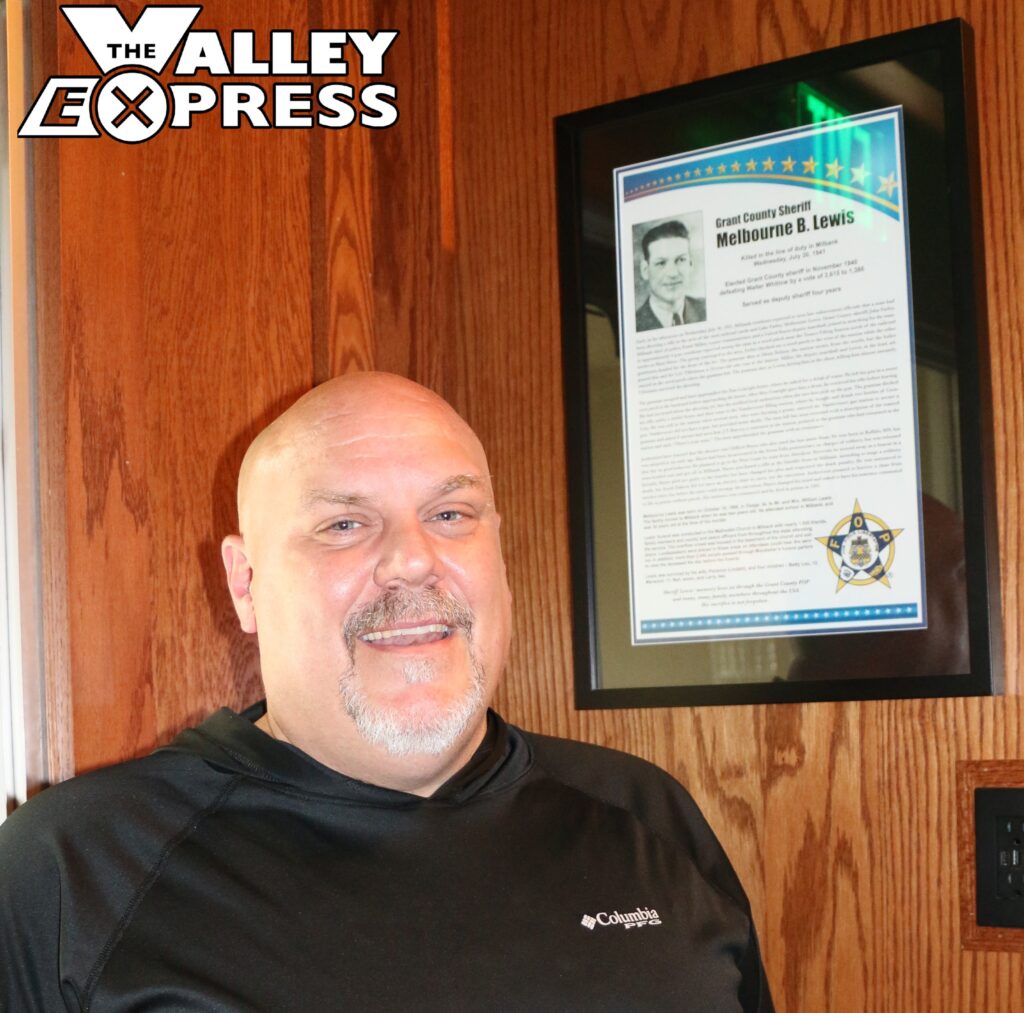

Bob Schultz of Milbank, great-grandson of Melbourne (his grandfather was Marwood), has been chronicling the history of the Lewis family for years. He has collected binders full of stories, photos, news clippings, and other bits and pieces that create a family tapestry. He also displays an homage to Sheriff Lewis on the wall at The Pump 2.0, Bob’s restaurant in downtown Milbank.

Bob reflected on how the tragedy shaped his family, “A lot of people thought Florence was stern. Maybe she was. Maybe she had to be.” Bob, however, fondly looks back on her as a grandmother –his great grandmother to be precise. He said, “I remember staying at Grandma Florence’s house when I was six or seven years old. Not a lot of memories, but good ones. I knew where I slept. I knew where the treats were. The whole house is still in my head. I had really good times in that house. I didn’t sense any unhappiness.”

Lori also recalls the days when Grandma Florence lived in that gray house . She says, “My memories of her are warm. I remember sitting on her lap and her hugging us and reading stories.”

Everyone in the Lewis clan seems to readily agree that even today a trip to the Grant County Courthouse floods them with pleasant childhood memories of visiting Grandma Florence at work. They especially like to think about when they would run up the marble steps with the black iron railings.

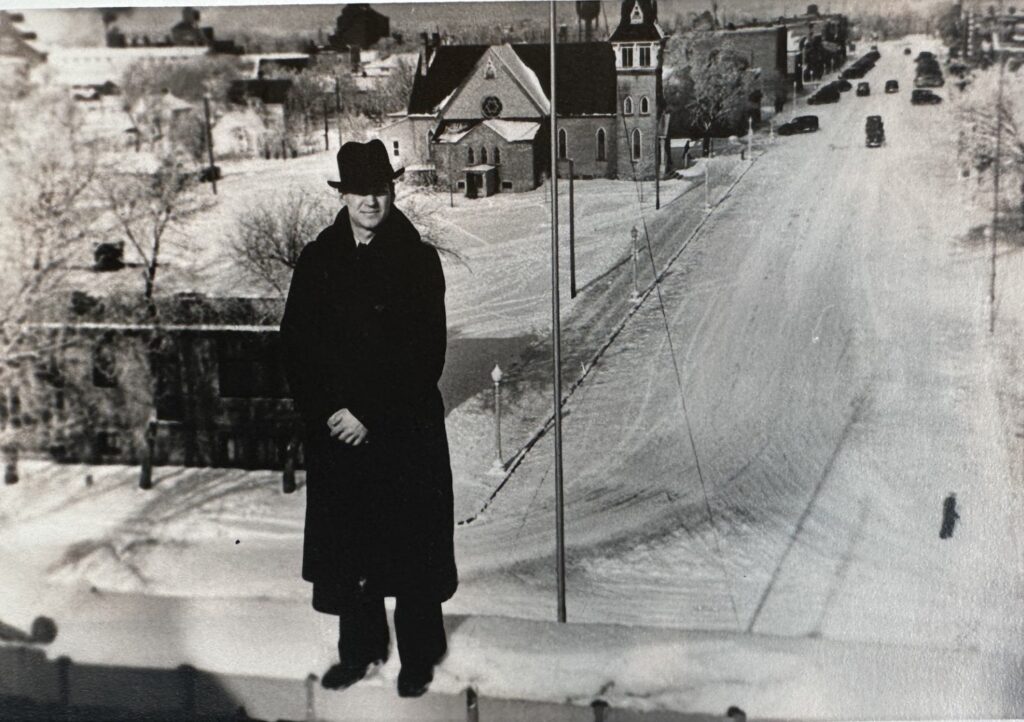

They also each uncannily selected the same family photo of Melbourne as their favorite. In the black and white snapshot, Melbourne is standing on a ledge on top of the courthouse in the snow and looking north up Milbank’s Main Street. Was he prescient? Was he stopping time to send a special and everlasting message to his family? No one knows the answer, of course, but a deep bond was forged.

“From the vantage point of my business on Main Street, I can look out the window and see down to the courthouse,” Bob said. “That means a lot. It’s very symbolic to me.”

Bob said he believes his great grandparents’ tragedy galvanized the Lewises’ commitment to their family, their community, and their country. And it inspired their willingness to step up in whatever capacity they were called upon to serve.

“My grandfather Marwood graduated from MHS in 1948. He then took the train to Fargo and joined the Navy. I joined the Navy. All four of my kids joined the Navy.”

In 1952, Marwood was selected as an AM2 for the Blue Angels Enlisted Flight Crew. He was a veteran of the Korean War and was deployed for three tours of duty in Vietnam. In 1987, Captain Lewis retired after 39 years, two months, and 23 days of continuous active duty service. Marwood died in December 2017.

Melbourne’s sister Betty Lou married Francis Chaloupka and they moved to Rapid City in 1950. In 1972, she and her family narrowly survived the devastating Rapid City Flood. It is remarkable, considering Betty Lou went through not just one, but two monumental tragedies in her life, that the first thing people always said about her was that she never had a negative thing to say about anyone or anything. Betty Lou passed away in July 2017.

As a boy, Neil had spent his summers working as a farmhand. At 19, after he graduated from MHS, he worked for Bell Telephone. Lori said, “ I think my dad was the more mellow one.” But people in the Milbank community remember him as a mover and shaker. While still a young man, Neil purchased Louie’s Standard Oil station in Milbank. He also established Top Hat Bowling Lanes along Earl Bohlen in 1958. Neil, Bohlen, and Jack Stengel also invented granite bowling lanes and granite topped billiard tables. Neil and Bohlen founded Whetstone Realty in Milbank in 1960. Neil later spent two years traveling to Ethiopia developing a project to obtain gum arabic.

Neil is also remembered for spearheading an all-volunteer group to build football bleachers at MHS in 1972. After moving to Rapid City in the early 1970’s, he owned and operated the Esquire Dinner Club and created the franchise International Mergers and Acquisitions (IMA). Neil died in December 2020.

Larry, now 86, who bears the middle name of Melbourne, lives in Rapid City where, as his great-nephew Bob, said, “He helped develop half of Rapid City with his business partners.” Larry’s son Randy is the only South Dakota wrestler to win Olympic Gold.

Florence (Lindahl) Lewis died in 1985 in Milbank.

As to the fate of Hayes, in 1941, he was the first person in South Dakota in 27 years to be sentenced to the death penalty. He was to die by electrocution, however, South Dakota did not own an electric chair and they also encountered difficulty obtaining an operable electric chair from another state. The execution was delayed. Hayes then petitioned the court again to commute his sentence to life in prison without parole. He lived for another 50 years in the South Dakota Penitentiary and died there in 1993.

Sheriff Melbourne Lewis, according to records dating from February 14, 1884, to 2024, is one of the 70 law enforcement officers who have died in the line of duty in South Dakota. He is one of only eight sheriffs and deputy sheriffs who was intentionally killed –shot or stabbed.

National Law Enforcement Appreciation Day is observed annually on January 9. Today, we thank all law enforcement officers – especially those in our Milbank Police Department, Grant County Sheriff’s Office, and South Dakota Highway Patrol, who bravely go out every day in their efforts to protect and serve.

We also pause to remember and thank all members of law enforcement from the past. Moreover, we pay tribute to Sheriff Melbourne Lewis, the man who made the ultimate sacrifice for the people of Grant County and South Dakota.

History is not a burden on the memory, but an illumination of the soul. – John Dalberg Acton

Photos: Top- Steve Lewis, Lori Lewis Dockter, Sheri Lewis Wendland, Melbourne “Mickey” Lewis.

Bottom-Bob Schultz.

All Other Photos Courtesy of The Lewis Family.

No comments so far.

Be first to leave comment below.