The Milbank Water Department Goes With the Flow to Keep Milbank Functioning

Local News May 21, 2021 Staff 0

This week, May 16-22, is National Public Works Week. It calls attention to the importance of vital community facilities and systems such as drinking water, wastewater, and storm water, and it recognizes the dedicated workers who make these services possible. When all is functioning properly, these workers remain anonymous and often go unnoticed even in small towns and cities.

The Valley Express salutes all the public works employees in Milbank and applauds Don Settje and Ron VanHoorn — two of Milbank’s public works employees responsible for keeping things running smoothly.

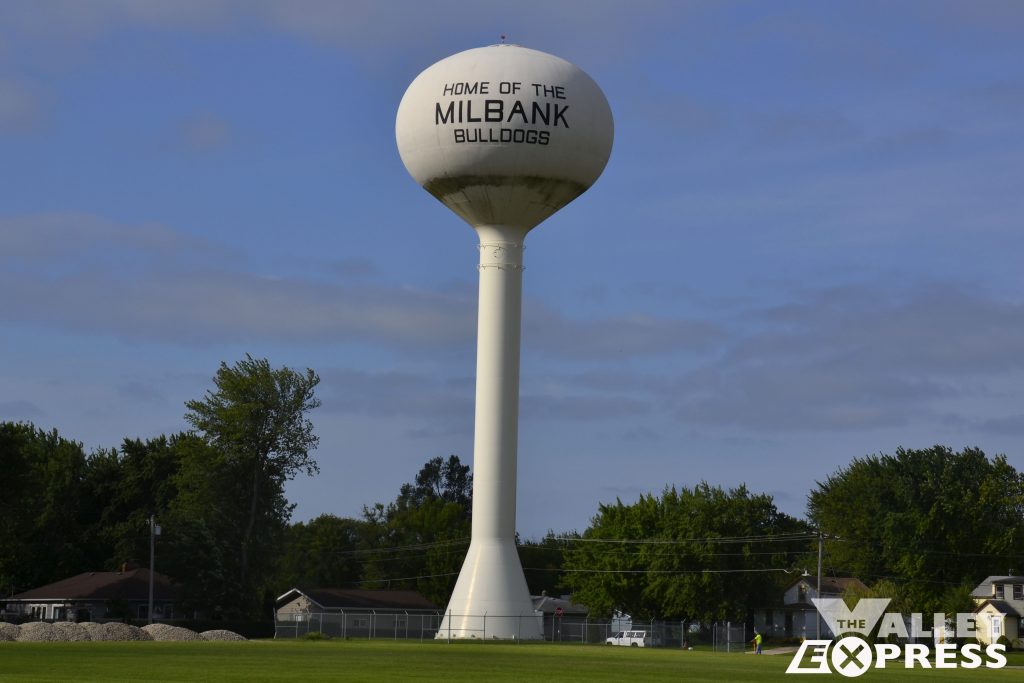

If you drive across South Dakota, you’ll notice a variety of water towers. They jut out from the flat grasslands of the prairie like beacons to guide you to the town that lies just ahead. Rapid City’s tower proclaims the city as The Star of the West. Mitchell touts itself as Home of the Corn Palace. And, sure enough, Tea’s water tower features a fancy little teapot. Well, maybe it’s not so little.

If you happen to be mechanically challenged, you might wonder: Why in the world do we store our water up so high? Why doesn’t it tip over? Or, when the thermometer reads 20 degrees below zero, why doesn’t the water freeze? Don Settje, manager of the City of Milbank’s water department, has been maintaining Milbank’s water tower for over 20 years. He knows the answers to those questions and more. Settje says Milbank’s water tower is a typical multi-column design. It was built in 1988 and is made entirely of steel. He explains: “A water tower is essentially a simple machine. Clean water is pumped up into the tower, where it’s stored in a tank. Milbank’s tank holds 400,000 gallons.” (An average in-ground swimming pool holds 20,000 gallons.) When the tank receives a request for water from a resident, the pump uses the force of gravity to create water pressure. Because the system needs to work with gravity, it must be taller than the surrounding buildings. Storing the water high above the ground also means a smaller water pump can be sufficient. Demand for water ebbs and flows throughout a typical day. Do you take a shower in the morning? Most people do. But, do you use a lot of water at 4 a.m.? If the water was stored at ground level, the city would need a larger and more powerful pump to keep pace with peak-time usage.

Settje says, “Milbank’s peak times are in the morning and also at night in the summer, when people tend to water their lawns and gardens.” He says, all in all, Milbank uses about 650,000 gallons a day. During low-demand times, the water tower replaces the depleted water level. Thus, when demand increases again, gravity can do more of the work without requiring so much help from the pump. Every foot the water tower rises results in an increase in water pressure of about .43 pounds per square inch. What if there’s a problem with the pump? Settje says the water in the water tower would last Milbank about half a day. But, he says there’s little danger of an issue occurring due to the failure of the pump. Milbank’s water department incorporates redundancy as a safety measure. The tower has three pumps, but the trio isn’t used all the time. Two of the units are considered backup pumps. There is also a backup generator to cover that contingency. How does he stop the water tower from tipping over? Settje says we keep the weight balanced. The structure also features strong support.

How does he manage to keep the water from freezing when temperatures dip down low? “We adjust the water flow. When it’s cold out, the water tower gets filled more to make sure the water level is up to at least 24 feet.” That constant flow in and out continues to move any ice and keeps it from building up. Also, the water doesn’t freeze because there is so much of it. It acts as a thermal mass to retain the heat. But, if they didn’t keep it moving, it would eventually freeze.

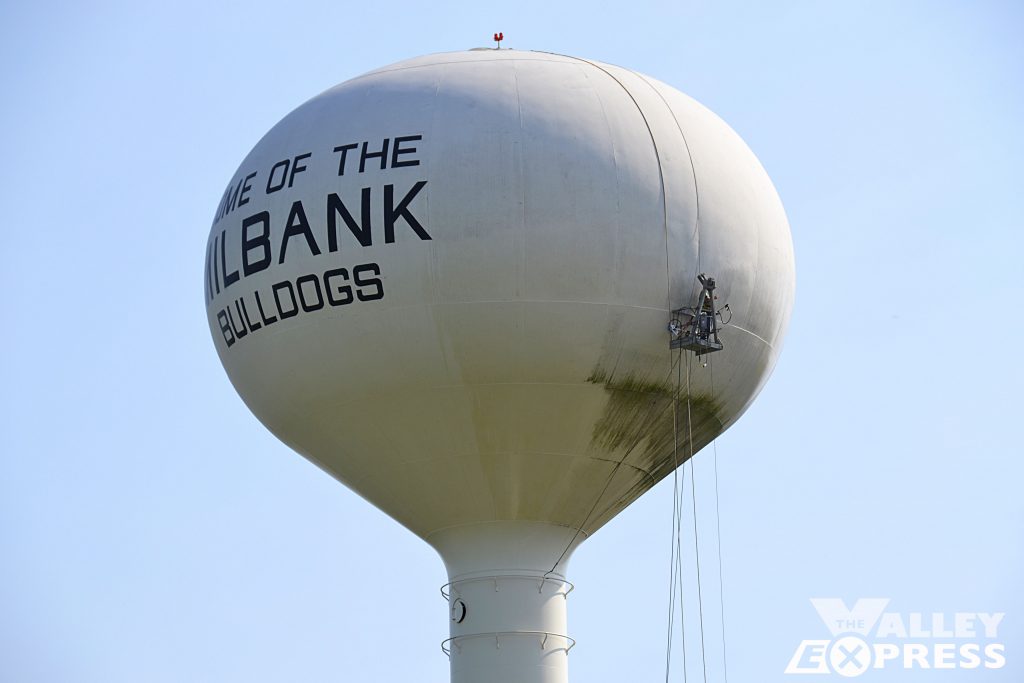

How does the water tower get cleaned? Settje says, “The City of Milbank signed a maintenance contract with the Maguire Iron Company in Sioux Falls. They power wash it according to the schedule.” How often does the water tower get painted? Settje says, “It needs to be painted about every 15 years, and it’s due to be repainted in the next couple of years.”

Will Milbank go back to emblazoning theirs with The Birthplace of American Legion Baseball? It’s an interesting question, but not a decision made by the water department.

How often do the lightbulbs need to be changed? That answer came from Ron VanHoorn. Van Horn’s job is to provide city-wide maintenance for all the departments. He says, “Donny (Settje) asked me if I wanted to change the bulbs or if he should hire a company to come to Milbank to do it.” “Not too many people around here would say ‘today seems like a good day to climb 142 feet to change a couple of light bulbs,” VanHoorn laughed and continued. “But, I look at it as part of my job. I’m lucky enough to have a job, so I’ll do what I have to do.” Does he suffer from a fear of heights? “I’m not the hugest fan,” he said, “but I had harnesses on so I felt pretty safe.” Spoiler alert: If you suffer from acrophobia— the fear of heights — even reading the next few paragraphs might make you feel dizzy and break out in a cold sweat. First of all, as VanHoorn mentioned, it’s 142 feet up. Up steps that are in the center of the water tower. Just calling them steps is a stretch, though. It’s more like climbing a ladder, and it’s a system of ladders. So, it’s open and you can see all the way down all the time.

On bulb-changing day, Settje stayed at the bottom, but another co-worker followed VanHoorn up to the first level. VanHoorn had strapped on a fanny pack to carry the light bulbs and a rope. “That way, he says, “ I didn’t have to go all the way back down if I needed something. We worked together and figured it all out. It was a group effort.” He described the bottom level as one flight of steps of about 20 feet that somewhat go at an angle. He says the first flight wasn’t bad. The second flight is about 60 feet up. “But,” he said, “When I got about halfway up I started to wonder. ‘What was I thinking? Maybe I should start working out again tomorrow.’ Then, I got to the stem piece that has another whole flight of steps and another level after that. The last set of steps is right in the center of the water tower. The last stage also has a 42-inch pipe with a set of ladder steps in the middle of it.” He explained how the first two stages have a cage over them and provide a place to sit back a bit, rest your arms, and lean some. But, on the last segment there’s only a round tube just 42 inches in diameter, and there is no place to lean. He says, “When I went up that last flight I was fighting on every step trying to get comfortable and catch a break. I knew I just needed to get to the top and told myself, ‘Don’t look down’” “But,” he said, “I had so much safety equipment on, the tower would have probably fallen over before I did.” “It’s tricky once you get up there,” says. There’s a cable that runs up the ladder that attaches to you. So if you fall, it’s a braking system. When you get there, you have to tie it off with another lanyard. That lets you get up higher, because you’re still a little low to pop yourself out the door. To change the bulbs, you need to go beyond where the cable actually reaches to get to the light fixtures.” He says when he got to the top hatch, he was tall enough so he didn’t have to crawl out on top of the tower. He could stand on the ladder and reach out. The two lights are located about three feet up on the outside of the tower. “No problem,” he says, “Except, on top, the wind was blowing like a hurricane! The velocity on the ground was probably only about five mph, but the wind intensifies when it hits the tower and travels over it.” He says he put in one LED and one filament long-lasting bulb as an experiment to test which one will last longer. Coming down was definitely easier than going up he admits. “Gravity helps a lot. I just needed to take my time and make sure I didn’t miss a step. The entire process took less than an hour.” His modesty is refreshing as he keeps insisting it was all a joint effort. “I’m just the guy that went up there. I climbed some steps and changed some bulbs.”

Fortunately, the bulbs are expected to last 10,000 hours, which he estimates is about four years, because he says, “It’s not something I want to do every day of the week.” An interesting comment in lieu of the fact he climbed almost to the top of the tower the day before to also replace all five of the bulbs on the inside. While replacing the outside bulbs, he even had the wherewithal to soak in the scenery. “It was hazy,” he says, “but on a clear day you can see the Marvin hills.”

Someone joked and said, “They probably need the bulbs replaced on the 825-foot FM tower up by South Shore.” VanHoorn just laughed and said, “I’m glad that one is outside the city limits!”

Photo: Ron VanHoorn, Trey Jankert and Don Settje

No comments so far.

Be first to leave comment below.